This is an updated version of a previous post. The main findings have been published today as a rapid response in the British Medical Journal.

We have recently

discovered that UK laboratories have been routinely recording a significant

proportion of Covid-19 test results as positive based on the presence of one

target gene alone, when there should have been two or more, as required to

comply with WHO rules and manufacturer instructions. Without

diagnostic validation, for both the original virus and any variants, it is not

clear what can be concluded from a positive test resulting from a single target

gene call, especially if there was no confirmatory testing. Given this, many of

the reported positive results may be inconclusive, negative or from people who

suffered past infection for SARS-COV-2

An academic pre-print of article available here and also on arXiv

The full article is reproduced below:

Positive

results from UK single gene PCR testing for SARS-COV-2 may be inconclusive,

negative or detecting past infections

Prof.

Martin Neil,

School

of Electronic Engineering and Computer Science,

Queen

Mary, University of London

18

March 2021 (version 7)

Abstract

The UK Office for

National Statistics (ONS) publish a regular infection survey that reports data

on positive RT-PCR test results for SARS-COV-2 virus. This survey reports that a

large proportion of positive test results may be based on the detection of a

single target gene rather than on two or more target genes as required in the manufacturer

instructions for use, and by the WHO in their emergency use assessment. Without

diagnostic validation, for both the original virus and any variants, it is not

clear what can be concluded from a positive test resulting from a single target

gene call, especially if there was no confirmatory testing. Given this, many of

the reported positive results may be inconclusive, negative or from people who

suffered past infection for SARS-COV-2.

Background

The efficacy of mass

population testing for SARS-COV-2 virus is critically dependent on the

reliability of the test applied, whether it be a RT-PCR or lateral flow test.

Given that many RT-PCR tests do not actually target all the genes necessary to

reliably detect SARS-COV-2, the results of mass testing using RT-PCR need to be

revisited and reanalysed.

The ONS publish a regular

infection survey [1], [20] that includes data from two UK lighthouse

laboratories, based in Glasgow and Milton Keynes, where both use the same

RT-PCR test kit, to detect the SARS-COV-2 virus. This survey includes data on

the cycle threshold (Ct) used to detect positive samples, the percentage of

positive test results arising from using RT-PCR, and the combinations of the SARS-COV-2

virus target genes tested that gave rise to positives between 21 September 2020

and 1 March 2021 across the whole of the UK.

The kit used by the

Glasgow and Milton Keynes lighthouse laboratories is the ThermoFisher TaqPath RT-PCR which tests for the

presence of three target genes from SARS-COV-2 [11]. Despite Corman

et al [2] originating the use of PCR testing for SARS-COV-2 genes there is no agreed

international standard for SARS-COV-2 testing. Instead, the World Health

Organisation (WHO) leaves it up to the manufacturer to determine what genes to

use and instructs end users to adhere to the manufacturer instructions for use

(IFU). As a result of this we now have an opaque plethora of commercially

available testing kits, that can be applied using a variety of test criteria.

Other UK laboratories use different testing kit, and test for different genes.

The WHO’s emergency use

assessment (EUA) for the ThermoFisher TaqPath kit [3] includes the instruction

manual and contained therein is an interpretation algorithm describing an unequivocal

requirement that two or more target genes be detected before a positive result

can be declared. This is shown in Table 1. The latest revision of

ThermoFisher’s instruction manual contains the same algorithm [21].

Table

1: Screenshot of results interpretation ThermoFisher TaqPath IFU on page 60 of

[3] (their Table 6)

The WHO have been so concerned

about correct use of RT-PCR kit that on 20 January 2021 they issued a notice

for PCR users imploring them to review manufacturer IFUs carefully and adhere

to them fully [4].

Increasing proportion of

single gene target “calls”

The ONS’s report [1]

lists SARS-COV-2 positive results for valid two and three target gene

combinations

and does the same in [20], for samples processed by the Glasgow and Milton

Keynes lighthouse laboratories. However, it also lists single gene detections

as positive results

(See tables 6a and 6b). This use of single gene “calls” suggests that these

lighthouse laboratories may have breached WHO emergency use assessment (EUA)

and potentially violated the manufacturer instructions for use (IFU). According

to the WHO, such single gene calls should be classified as inconclusive test

results. However, Section 10 of this ONS Covid-19 Infection survey report [5] on

the 8 January 2021 stated that one gene is sufficient for a positive result

(emphasis mine):

“Swabs

are tested for three genes present in the coronavirus: N protein, S protein and

ORF1ab. Each swab can have any one, any two or all three genes detected.

Positives are those where one or more of these genes is detected in the

swab …..”

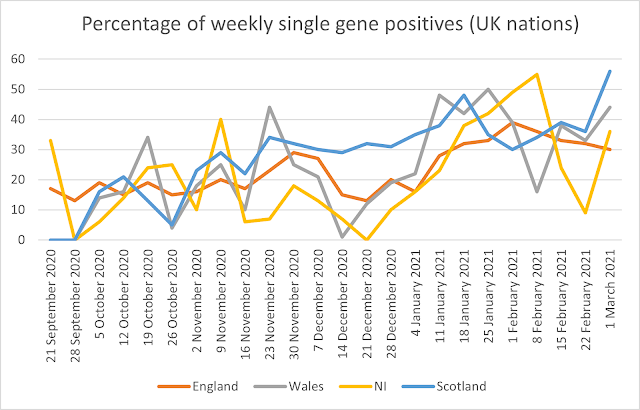

Over the period reported

the maximum weekly percentage of positives on a single gene is 38% for

the whole of the UK for the week of 1 February. The overall UK average was 23%.

The maximum percentage reported is 65%, in East England in the week beginning 5

October. In Wales it was 50%, in Northern Ireland it is 55% and in Scotland it was

56%. The full data including averages and maxima/minima are given in Table 2.

Figures 1 and 2 show the percentage

of weekly single gene positives across the UK nations and English regions.

There has been a significant increase in the percentage of single gene

positives since the end of 2020, rising from January, and here the rise is

steady across all English regions and UK nations.

Table

2: Percentage of weekly single gene positives from 21 September 2020 to 1 March

2021, including averages and maxima/minima

Figure

1: Percentage of weekly single gene positives from 21 September 2020 to 25

January 2021 (UK nations)

Figure

2: Percentage of weekly single gene positives from 21 September 2020 to 25

January 2021 (English regions)

Professor Alan McNally,

Director of the University of Birmingham Turnkey laboratory, who helped set up

the Milton Keynes lighthouse laboratory, contradicted what was stated in the

ONS report in a Guardian newspaper article about the new variant. He reported

that all lighthouse laboratories operated a policy that adhered to the

manufacturer instructions for use: requiring two-or-more genes for positive

detection [6] (this policy is also documented in [22], which defines the

standard operating procedure reported in [7]).

In correspondence with Mr Nicholas Lewis about single

gene testing, in February 2021, the ONS confirmed that they do indeed call

single gene targets as positives in their Covid-19 Infection Survey and also

confirmed that the samples are processed by UK lighthouse laboratories [8],

[9].

As early as April 2020,

the UK lighthouse laboratories were testing for single genes and discounted the

S gene as early as mid-May [10], months before the discovery of the new variant

B1.1.7 (emphasis mine):

“Swabs

were analysed at the UK’s national Lighthouse Laboratories at Milton Keynes

(National Biocentre) (from 26 April) and Glasgow (from 16 August) …., with

swabs from specific regions sent consistently to one laboratory. RT-PCR for

three SARS-CoV-2 genes (N protein, S protein and ORF1ab) ..... Samples are

called positive in the presence of at least single N gene and/or ORF1ab

but may be accompanied with S gene (1, 2 or 3 gene positives). S gene is not

considered a reliable single gene positive (as of mid-May 2020).”

Indeed, in Table 1 of [10]

18% of tests were positive on one gene only and it was concluded, in Table 2 of

[10] that, for people with single gene positives, when Ct > 34, none had

symptoms and for people with Ct < 34 only 33% had symptoms.

Furthermore in a Public

Health England report on variants [11], published January 8th 2021,

it states the goal of using one gene was explicitly to approximate the growth

of the new B1.1.7 variant (emphasis mine):

“There

has recently been an increase in the percentage of positive cases where only

the ORF1ab- and N-genes were found and a decrease in the percentage of cases

with all three genes. We can use this information to approximate the

growth of the new variant.”

Quality control and cross

reactivity

Quality control problems

have already been reported in UK laboratories [12, 13, 14] and concerns have

been expressed about the potential for false positives arising consequently.

Recent suspicion focused on problems potentially caused by exceeding acceptable

Ct thresholds, suggesting no, or past, infection. However, this new ONS data

shows there may be an additional potentially dominant source of false

positives, at least within the period covered by the ONS report, if not from

April 2020.

Concerns about testing in

commercial laboratories were documented by the ONS as early as May 2020 [15],

when the REACT study discovered that circa 40% of positive tests from

commercial laboratories were in fact false positives. A similar false positive

rate (44%) was reported in Australia [16] in April 2020. More recently Mr Nicholas Lewis claims that,

despite very low false positive rates (0.033%) from testing done by

non-commercial and academic laboratories, there may be reason to suspect the

operational false positive rates from lighthouse laboratories may be worse than

these by some orders of magnitude [17].

Obviously, there is a higher

risk of encountering false positives when testing for single genes alone,

because of the possibility of cross-reactivity with other human coronaviruses (HCOVs)

and prevalent bacteria or reagent contamination. The potential for cross

reactivity when testing for SARS-COV-2 has already been confirmed by the German

Instand laboratory report from April 2020 [18] (note that Prof. Drosten,

co-author of Corman et al [2] is a cooperating partner listed in this report).

The report describes the systematic blind testing of positive and negative

samples anonymously sent to 463 laboratories from 36 countries and evaluated

for the presence of a variety of genes associated with SARS-COV-2. They reported significant

cross reactivity and resultant false positives for OC43, and HCoV 229E (a

common cold virus) as well as for SARS-COV-2 negative samples, not containing any

competing pathogen. Likewise, 70 Dutch laboratories were surveyed in November

2020, by the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment [19],

with 76 diagnostic workflows reported as using only one target gene to diagnose

the presence of SARS-COV-2 (46% of all workflows).

Conclusions

Without diagnostic

validation, for both the original virus and any variants, it is not clear what

can be concluded from a positive test resulting from a single target gene call,

especially if there was no confirmatory testing. Many of the reported positive

results may be inconclusive, negative or from people who suffered past

infection for SARS-COV-2. Even with diagnostic validation of the single target gene

call, the UK lighthouse laboratories appear not to be in strict conformance

with the WHO emergency use assessment and the manufacturer instructions for use.

Given this it is clear the ONS and the UK lighthouse laboratories needs to

publicly clarify their use of, and justify the reasons for, deviating from

these standards.

References

[1] Steel

K. and Fordham E. Office for National Statistics. Coronavirus (Covid-19)

Infection Survey. 5 December 2020 (See tables 6a and 6b).

https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/datasets/coronaviruscovid19infectionsurveydata

[2] Corman

V., Landt O. et al “Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by

real-time RT-PCR” Euro Surveillance. 2020 Jan;25(3):2000045. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045.

[3] WHO

Emergency Use Assessment Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) IVDs. PUBLIC REPORT.

Product: TaqPath COVID‑19 CE‑IVD RT‑PCR Kit. EUL Number: EUL-0525-156-00. Page

60

https://www.who.int/diagnostics_laboratory/eual/200921_final_pqpr_eul_0525_156_00_taqpath_covid19_ce_ivd_rt_pcr_kit.pdf?ua=1

[4] WHO

Information Notice for IVD Users 2020/05. Nucleic acid testing (NAT)

technologies that use polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for detection of

SARS-CoV-2. 20 January 2021

https://www.who.int/news/item/20-01-2021-who-information-notice-for-ivd-users-2020-05

[5] ONS Coronavirus

(COVID-19) Infection Survey, UK: 8 January 2021. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/coronaviruscovid19infectionsurveypilot/8january2021#the-percentage-of-those-testing-positive-who-are-compatible-for-the-new-uk-variant

[6] Alan

McNally. “It's vital we act now to suppress the new coronavirus variant”

Opinion section the Guardian Newspaper, 22 Dec 2020. https://amp.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/dec/22/new-coronavirus-variant-b117-transmitting?CMP=Share_AndroidApp_Other&__twitter_impression=true

[7]

Richter, A., Plant, T., Kidd, M. et al. How to establish an academic

SARS-CoV-2 testing laboratory. Nat Microbiol 5, 1452–1454

(2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-020-00818-3

[8]

Dr John Allen, ONS. Email correspondence to information request from Dr Nicholas

Lewis, “Your ad hoc Covid-19 PCR gene detection analysis for the ONS”, 22

February 2021.

[9]

Zoe (?), ONS. Email correspondence to information request from Mr Nicholas

Lewis, ONS, email correspondence to information request from Mr Nicholas Lewis,

“ONS ad hoc Covid-19 PCR gene detection analysis”, 25 February 2021.

[10]

Walker S. Pritchard E et al. Viral load in community SARS-CoV-2 cases varies

widely and temporally. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.10.25.20219048v1

[11]

Public Health England “Investigation of novel SARS-COV-2 variant. Variant of

concern.”, 202012/01.

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/959438/Technical_Briefing_VOC_SH_NJL2_SH2.pdf

[12]

Daily Mail “Chaos in Britain’s Covid labs: Scientist lifts lid on government

facilities. 18 September 2020.

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8746663/Chaos-Britains-Covid-labs-Scientist-lifts-lid-government-facilities.html

[13]

Channel 4 Dispatches: Lockdown Chaos: How the Government Lost Control. 15th

November 2020

https://origin-corporate.channel4.com/press/news/dispatches-uncovers-serious-failings-one-uks-largest-covid-testing-labs

[14] BBC

News: Coronavirus testing lab 'chaotic and dangerous', scientist claims. 16

October 2020.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-54552620

[15] Riley

S. Kylie E, Ainslie O. et al. Community prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 virus in

England during May 2020: REACT study. July 2020. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.07.10.20150524v1

[16]

Rahman, H., Carter, I., Basile, K., Donovan, L., Kumar, S., Tran, T., ... &

Rockett, R. (2020). Interpret with caution: An evaluation of the commercial

AusDiagnostics versus in-house developed assays for the detection of SARS-CoV-2

virus. Journal of Clinical Virology, 104374

[17]

Lewis. N. “Rebuttal of claims by Christopher Snowden about False Positive

Covid-19 test results”. February 2020. https://www.nicholaslewis.org/a-rebuttal-of-claims-by-christopher-snowdon-about-false-positive-covid-19-test-results/

[18]

Zeichhardt H., and Kammel M. “Comment on the Extra ring test Group 340

SARS-Cov-2” Herausgegeben von: INSTAND Gesellschaft zur Förderung der

Qualitätssicherung in medizinischen Laboratorien e.V. (INSTAND Society for the

Promotion of Quality Assurance in Medical Laboratories e.V.) 3rd June 2020.

https://www.instand-ev.de/System/rv-files/340%20DE%20SARS-CoV-2%20Genom%20April%202020%2020200502j.pdf

[19] External

Quality Assessment of laboratories Performing SARS-CoV-2 Diagnostics for the Dutch

Population. National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, Ministry

of Health, Welfare and Sport., November 2020.

https://www.rivm.nl/sites/default/files/2021-02/EQA%2520of%2520Laboratories%2520Performing%2520SARS-CoV-2%2520Diagnostics%2520for%2520the%2520Dutch%2520Population%2520November-2020.pdf

[20] Walker, S. 21 December 2020.

Covid-19 infection Survey: Ct values analysis (Glasgow and Milton Keynes

identified in Table 4a) https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/adhocs/12692covid19infectionsurveyctanalysis

[21] TaqPath COVID-19 Combo Kit and

TaqPath COVID‑19 Combo Kit Advanced INSTRUCTIONS FOR USE. Revision J.0, 22

February 2021. (See Table 25, page 107). https://assets.thermofisher.com/TFS-Assets/LSG/manuals/MAN0019181_TaqPath_COVID-19_IFU_EUA.pdf

[22] Clinical Immunology Service,

University of Birmingham. ‘Competency Assessment: Reporting, Interpretation and

Authorisation of Results in Turnkey Birmingham’. CIS/TK44, v1.0. September

2020.